Volume 3

Commercial use of the round nose bar was initiated with the Wolf machine. The manual shows an interesting drawing of the bar which is reproduced herein. The frame, as the bar was then called, was constructed of 4 pieces of special saw steel riveted together and heat treated and hardened to a Rockwell test of 53 – 56. A detachable handle was provided for the round nose end which could be removed for boring.

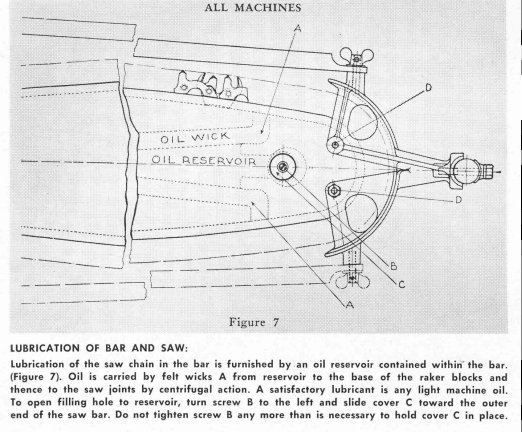

A special feature was in oil reservoir in the bar. As the drawing shows, outlets were provided at the top and bottom of the bar adjacent to the nose end. These outlets lubricated the chain and bar before the chain entered a cut instead of afterwards as it is done today. The top outlet fed oil to the chain before it entered a boreing cut. Both outlets supplied oil to the chain before entering horizontal and vertical cuts. With the outlets so located, top and bottom, lubrication was assured when the bar was periodically inverted to equalize wear. This and another important feature are explained by Mr. Wolf.

“Obviously, the quantity of oil that could be supplied by this method was less than that provided by present day chain saw force feed systems. However, the chain and bar were designed so that less lubrication was required than is necessary today. Moreover the chain was oiled before entering a cut as it should be. Oiling a chain after it emerges from a cut, as it is done today, can result in a considerable loss of lubricant because it is thrown off the chain as it travels over the free or top side of the bar.

“With a Rockwell hardness of 53 – 56, the round nose end of the bar could not withstand boreing without damage. Hardening materials and processes for a bar nose common today were not then available. As a result, damage prevention was achieved by means of a special nose design related to the chain linkage. In other words, damage prevention was achieved by means of design instead of by material and process. The record shows that there was no known nose damage during the history of the machine.

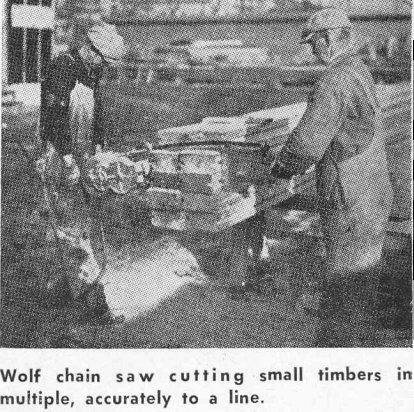

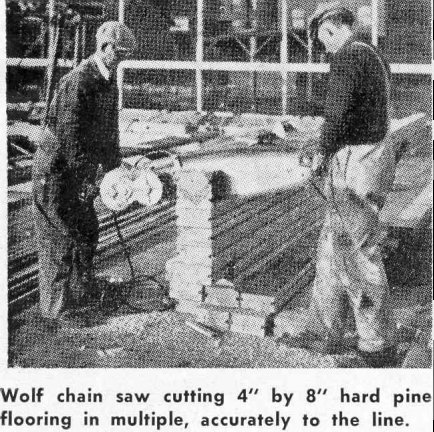

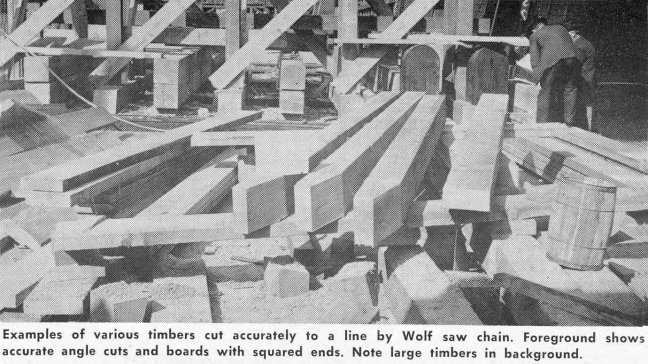

As mentioned in the previous article, the Wolf chain made an accurate line cut at any angle and also efficiently performed such non-precision cutting as logging. It was reversible which prolonged its life and reduced filing. The kerf it cut was only 5/16 of an inch (0.79 mm) and the cutting rate approximated that of the present conventional chain. Conversations with Mr. Wolf disclosed some additional information regarding the chain design.

“ In addition to efficiency, economy, minimum chain maintenance, and accurate line cutting, very careful consideration was given to other factors. For instance, the design provided an exceptionally smooth performance. The chain never grabbed or caused the machine to kick back when boreing or making any other kind of a cut. In other words, it was remarkably safe. In fact there is no record of any chain breakage or, what is more important, any injury resulting from that or any other cause.”

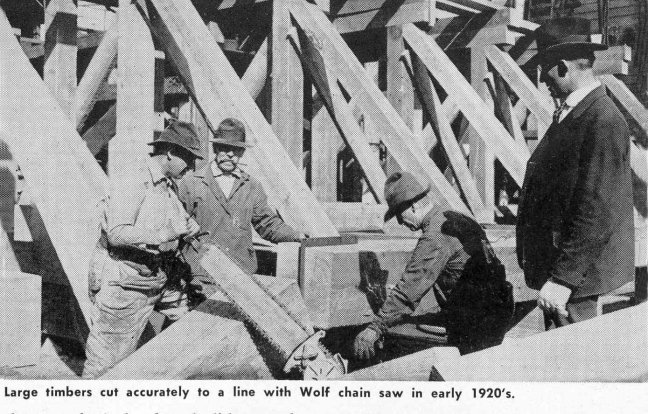

Copies of Wolf advertising literature indicate that it was attractive and executed in a first class manner. However, it was somewhat conservative in comparison with such material today. It consisted of single sheets and 4 to 8 page brochures. Both types showed the various machine models with each illustration accompanied by specifications indicating the quality of workmanship and material.

Brochures also contained photographic reproductions of machines performing accurate line cutting or non-precision work. Each illustration was accompanied by brief information concerning the type, condition and dimensions of the timber cut and the time required. The conservative aspect of this literature prompted questions to which Mr. Wolf supplied the answers.

“Our customers were firms and governments who were interested in the machine as a money saving tool. They required and appreciated factual information. Any approach other than factual would have been ineffective and probably would have alienated them. The machine lived up to the claims made in the literature, consequently, the business steadily increased even during the depths of the depression in the 1930’s.

“Publication advertising was more or less limited to the ENGINEERING NEWS RECORD. This was the best and the only effective medium available at the time. If a publication had been available, such as, the CHAIN SAW AGE, there is little doubt that sales could have been increased.”

A 1933 Wolf price list is very revealing. Retail prices for the machine varied with the cutting capacity of the bar. At that time, bar capacities were 16” (40 cm), 24” (60 cm), 36” (91 cm), 42” (106 cm) and 48” (122 cm). The retail prices of electric machines ranged from $495.00 to $860.00 and pneumatic machines from $595.00 to $975.00. The relatively few gas-engine machines sold were in the same price bracket. Electric and pneumatic with a 24” (60 cm) bar the most popular and retailed for $560.00 and $645.00 respectively.

The saw chain, sprocket and bar retailed for about twice as much as their present day counterparts. Mr. Wolf was asked to explain the cause and effect of these seemingly high prices. “Production costs, for various reasons, were unavoidably high. Naturally, they were reflected in the retail prices. However, the particular trade that we had developed did not object to the substantial initial investment resulting from these prices. Besides, there were mitigating factors.

“For instance, the cost of maintaining the electric and pneumatic power units was exceptionally low. Furthermore, the operational lives of the chain sprocket and bar were substantially more than that of their present day counterparts. Therefore, in the final analysis, the customer received then about as much per dollar invested as he does today.”

As this series of articles indicates, the original Wolf chain saw had several features that are not obtainable in any chain currently on the market. In view of this, Mr. Wolf was asked to explain specifically why the original chain and related components would not be competitive in today’s market.

“The chain design was such that the minimum, practicable chain pitch was 1” (2.54 cm) with a resultant sprocket diameter exceeding 5” (12.7 cm) and a bar width in proportion thereto. As a result, the size and weight of these components was considerably more than twice of such equipment for today’s portable machines. The size and weight of the Wolf components would render them inapplicable to the present portable machines and unacceptable to the trade. Furthermore, the chain and sprocket, in particular, would be too expensive to make.

“There was no way to reduce the pitch, size and weight of the original Wolf chain without destroying efficiency and other essential factors. Nevertheless, certain firms, individuals and a government agency naively attempted such modifications. It was inevitable that their efforts resulted in total failure.”

The foundation of a new great industry was the Wolf saw chain and the cornerstone, of course was the saw chain. As a previous article mentions, the passing of Charles Wolf marked the end of a colorful and dramatic chapter in the history of the industry. Considering all the handicaps in retrospect, it seems almost incredible that the chapter was ever written. Perhaps, the new saw chain developed and patented by Jerome Wolf will write another chapter.

(Editor’s note-In the next chapter of the Wolf Saga, the reporter discloses a new revolutionary Wolf chain saw development.) |